Filed under: Real Science Content, Speculation, Uncategorized | Tags: electrofishing, plesiosaurs, Speculative paleontology, Tanystropheus

I’m venturing back into the land of speculative paleontology with a modest suggestion about the reason why two groups of aquatic Mesozoic animals had ridiculously long necks. Some of these animals are very familiar: plesiosaurs. Some Plesiosaurs, members of the Plesiosauroidea, had ridiculously long necks. This trait was shared with the lesser known Triassic Tanystropheids, such as Tanystropheus longobardicus. Their necks are typically relatively stiff and weakly muscled, which gives rise to real questions about how the animal used them. Plesiosaurs, for example, could not raise their necks out of the water in the classic Loch Ness Monster or “swan” pose, nor could they sinuously retract their necks as if they were snakes’ bodies. Tanystropheus’ neck was even more limited, being compared to the stiff tails of hadrosaurs.

How did they use these necks? Proposals include Elasmosaurus “conceal[ing] itself below the school of fish. It then would have moved its head slowly and approached its prey from below” (from Wikipedia) to Tanystropheus fishing from marine shores as some sort of dipsy-diver, dropping its head down into the water from above. More bizarrely, taphonomic evidence in the form of fossilized sea floor gouges suggests that Plesiosaurids with long stiff necks were benthic feeders like rays or grey whales, grabbing their prey out of the mud (from Tet Zoo 2.0). It is hard to image an animal less adapted to such a hunting mode.

This doesn’t even get into the exquisite vulnerability of this body shape. Long, thin, stiff necks are very vulnerable to aquatic predators. Indeed, multiple artists have illustrated elasmosaur necks as the chew toys of large pliosaurs, and it is hard to imagine Tanystropheus surf fishing without getting its neck dislocated.

I’d like to suggest a different hypothesis, that these long, stiff necks were perfectly functional, and that, indeed, there are animals today that have similarly constrained morphologies. They aren’t tetrapods though, they’re fish. Electric fish, to be precise. Electrogenic organs have evolved at least four separate times in fish (Gymnotiformes, Mormyridae, Malapteruridae, Torpediniformes), and occur in both salt and freshwater. The South American knifefish (Gymnotiformes) are a particularly good example. As a group they have linear, fairly stiff, poorly muscled bodies. The apparent explanation for their shapes relates to the complexity of interpreting information from electric fields, and simpler body shapes make for more unambiguous signals. It appears that most electrogenic animals (animals that actively generate an electrical field for sensory purposes) have stiffer bodies with simpler shapes than do their less shocking relatives. This is also true for manmade electrogenic sensors, as a simple shape makes for a simple, easily interpretable field.

If the long stiff necks of Plesiosaurids and Tanystropheids are electrogenic organs, the weaknesses of the necks become strengths. Their necks’ main job is to be held stiff and straight in the water, and they appear well-built for this task. Moreover, electrogenic organs are built from stacks of electrocytes, which were the inspiration for batteries. The longer the neck, the more “batteries” it can hold, the bigger a field it can create, and the higher a voltage it can generate. The advantages don’t stop there. Electrogenic organs have three potential functions: sensing, electrofishing, and defense, and I will explore each in turn.

Active Electrolocation

Many animals can detect electrical fields, with or without special organs. Humans can detect sufficiently strong electric fields, while everything from catfish to sharks and rays to platypuses and river dolphins have structures specialized in passively detecting weak electrical fields. Electrogenic animals all actively use their electrical organs to sense their environments, feeling differences in the field due to the presence of things that either are either more or less conductive than the surrounding water. They can also detect the electrical fields innately given off by all animals through things like muscular exertion, heartbeats, or (in fish) the gill area. All of this adds up to a sophisticated electrolocation sense.

This is particularly important for animals that hunt in waters where vision is limited, either through turbidity or at night. It is also quite useful for hunting animals buried in the sediment, which is an explanation for the Jurassic sea-floor gouges caused by Plesiosaurids.

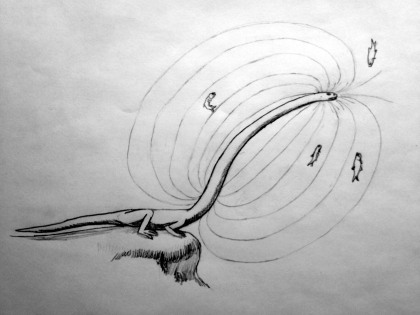

In an attempt to illustrate this, I chose the small (30 cm long) tanystropheid Tanytrachelos. This species was found in the Triassic, in the Solite Quarry in Virginia. It was apparently amphibious, for it was found in the sediments of a highly seasonal lake, and its webbed footprints are found fossilized in lake mud. Its main prey were apparently insects, and it apparently co-occurred with the fish Turseodus, of approximately the same size. Given the description of the lake sediments (alternating layers of mud and decayed vegetation), I suspect that the water wasn’t terribly clear, as it has been illustrated. The lake water may have been stained tea-brown by tannins, or it may have been muddied by rain and animal activity. Either way, I would suggest that Tanytrachelos was something like a platypus, an aquatic insectivore that found its prey using their electrical fields instead of eyesight.

I should note that all the long-necked species probably used electrolocation. It doesn’t take a large electric organ, and in turbid or dark environments it can be critical. It’s also possible that a majority of Plesiosaurids and Tanystropheids were electrolocators only. In modern electric fish, a majority are electrolocators, not active shockers, and there’s no reason to think this was different in the past. Certainly there is a tradeoff between carrying an electric organ and using a neck for something else, and there’s no reason to expect them all to be electrofishers. But some could have been.

Electrofishing

Here, I would like to compare the fish biologists’ standard sampling tool, electrofishing, with the biological versions. While it is not clear that electric eels hunt with their electric organs, marine torpedo rays certainly do. However, the best insight comes from human electrofishing. For those who are not familiar with it, electrofishing involves using a generator, a transformer, and at least two electrodes. When the system is properly tuned, fish are stunned and can be captured for population samples. Most electrofishing rigs work in freshwater, but several research groups practice marine electrofishing. Still, there are a number of complexities.

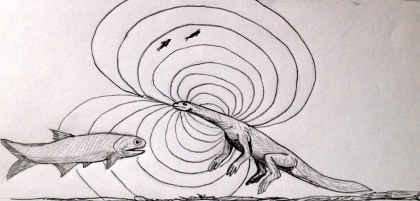

Human electrofishing works on a simple principle. Many fish, when caught in a pulsed DC field between a cathode and an anode, involuntarily swim towards the anode, a phenomenon called positive electrotaxis that is caused by involuntary muscle contractions in the fish. Fish biologists use this trick to draw fish into the anode area without killing them, so that they can count and measure them. Translating this to electrofishing animals, I propose that the animals used pulsed DC current, with the anode located immediately behind the head. If one looks at the field lines, this would cause fish to swim uncontrollably straight into the predator’s mouth. Additionally, electrofishing rigs are deliberately designed with the anodes as large as possible to avoid damaging the fish (reference). One could easily argue that the long, slender necks with small heads of animals like Elasmosaurus or Tanystropheus are the exact opposite, with small anodes evolved to stun, injure, or even kill the the prey before it reaches the predator’s mouth. I used Tanystropheus in the cartoon below to illustrate the principle, with the anode behind the animal’s head.

While this is simple in theory, it becomes complex in practice. For one, seawater conductivity varies depending on temperature and salinity. For another, fish catchability varies depending on the ratio of conductivity between the fish and the water, with a maximum efficiency where the fish has the same conductivity as the water. There are other factors, such as the frequency of the pulsed DC current used, which varies by fish targeted (usually determined empirically by biologists), and factors such as the thickness of the fish scales (thick-scaled fish are harder to catch this way) and the size of the fish (larger fish are more vulnerable than smaller fish) (reference). As an aside, it is not clear whether electrofishing works on squid or insects, apparently due more to lack of experimentation than anything else.

Thus, there is no one optimal design for electrofishing animals. Plesiosaurids could not broadly harvest every fish in the water, but would be constrained by how they could adjust to factors like salinity and the fish present, and I suspect that the substantial diversity they show represents adaptations to different electrofishing strategies. Most likely, the biggest plesiosaurids would have to migrate frequently to avoid fishing out local habitats and to take advantage of spawning clusters or feeding congregations, much as large sharks do today. Since a proportionally bigger electrofishing rig is required for oceanic uses, it suggests that freshwater electrofishers should have proportionally shorter necks. This appears to parallel the fossil record, where known estuarine or freshwater species have shorter necks than do marine animals.

As an aside, I get the impression that Mesozoic fish had thick scales compared to those of today. While this may be erroneous, it is possible the Plesiosaurid electrofishing caused adaptive pressure on Mesozoic fish to favor thicker scales than we find today.

Why are there so few electrofishing modern animals? I would suggest that the answer is aerobic capacity. Electric eels reportedly get 80% of their oxygen from the surface. They are air-breathers, more than some amphibians, but torpedo rays (the other electrofishers) are not. While I’m not aware of any physiological studies, large electrical organs have to be metabolically expensive, and being air-breathing does make it easier to power them However, electric eels are stuck morphologically, because they have to cram their all their organs into a shape optimized for electrogenesis, and they have heavily vascularized oral cavities rather than true lungs. Air-breathing reptiles are not so constrained. Better still, their electrical array is physically separated in their necks, away from their heart, lungs, and swimming fins, allowing each system to work separately with fewer morphological constraints. As a result, they could grow much larger than electric eels or any modern electric animal. As for how Plesiosaurids avoided electrocuting themselves with their own voltage, all I can say is that electric eels somehow get away with it, so presumably it’s quite possible. Some electrolocating fish have encephalization quotients close to those of humans, so it’s unlikely that electrogenesis would be a problem for Plesiosaurid nervous systems.

Electrical Defense

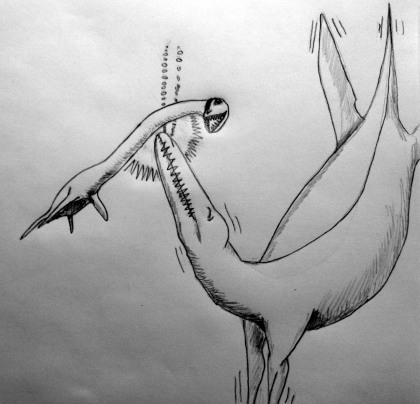

This is a normal outgrowth of electrofishing, although current characteristics probably differ. Indeed, more modern electrogenic animals use these organs for defense than for food gathering. This is the classic electric eel defense, and I suspect that any electrofishing animal could effectively defend its neck from larger predators. A pliosaur attempting to bite down on an electrogenic elasmosaur would be in for a nasty shock. I’ve attempted to illustrate that below, with my cartoon of what might happen when a Pliosaur attacks an Elasmosaurus.

An electrified Elasmosaurus teaching a Pliosaur that it is not a prey item (with apologies to Luis Rey and Robert Bakker)

In Conclusion

Of course this is all speculative, soft-organ paleontology. I haven’t been able to locate a picture of an electric eel skeleton, so I have no idea how electric organs affect bone shape, or whether it’s possible to determine the presence of an electric organ from any skeleton. Some Plesiosaurid neck vertebrae are described as “odd and asymmetric”, but I have no idea whether this could be due to the presence of an electric organ or anything else.

Still, the strength of this hypothesis is that it presents a good explanation of why both Plesiosaurids and Tanystropheids have long, weak, inflexible necks, and it also accounts for how such an animal could be an efficient aquatic or benthic hunter. As such, it is certainly no worse than the idea that they are stealthy hunters, with their bodies hidden by their long necks so that they appear smaller. In fact, it makes them seem rather formidable. Electric sea dragons, anyone?

Offline References

Bakker, Robert. 1986. The Dinosaur Heresies. Zebra Press.

Fraser, Nicholas. 2006. Dawn of the Dinosaurs: Life in the Triassic. Indiana University Press.

Filed under: livable future, Real Science Content, science fiction, Speculation, sustainability, Worldbuilding | Tags: Apocalypse, Deep Future, science fiction

I’ve gotten rather tired of the Mayan apocalypse, and being a contrarian, I’ve been thinking more about the deep future instead of the end of the world.

At some point, I made a sarcastic remark about wanting to write about a world “after the 34th apocalypse, except that I’m too lazy to come up with 33 separate apocalypses.” Now, as 12/21/12 comes closer, I’d thought it might be fun to crowd-source the other 33 apocalypses.

The idea of this is to provide future worlds for SF people to play with. Right now, I feel like SF is suffering from “aging white myopia” in that it’s mostly about the fears and fantasies of aging white people (often men), and myopia because most of the serious SF predictions are in the near future, not the deep future. I’d rather start thinking about 21st century problems, which are more about “how do we deal with this crazy world the Baby Boomers left us” than worrying about the death of the dreams we had as teens.

Want to play? Since I’m hoping to crowd source the apocalypses, I’m perfectly happy if people swipe ideas from here. This is about thinking creatively about global crises, and what comes after them.

Anyway, let’s get to the apocalypses

Here are the end points

1. The First Apocalypse is happening now, with a 5000 gigatonne release of carbon into the atmosphere over the next 200 years (this is the IPCC extreme scenario discussed here. This is the path we’re currently on. Temperatures (and extreme weather) peak between 2500 and 3500 AD, with global mean temperatures peaking 9 to 16 degrees F (6 to 9 deg. C) above today. Sea level rises about 230 feet (80 meters) above today, but it reaches that maximum in 3500 AD (almost all rise happens by 3000 AD). Conditions take 500,000 years to get back to what we have today, and we can assume the fall back towards normal in an approximately linear fashion. Thermal gradients between the arctic and the tropics largely disappear at first, but gradually reappear.

2. The 34th Apocalypse happens 525,000 years from now, when the next ice age starts. This is by fiat, from eyeballing the insolation graphs on Wikipedia. At this point, the last remnants of arctic and high mountain civilization are plowed under by the growing glaciers (antarctic civilization finally disappeared in 400,000 AD under the resurgent southern ice cap). This cycle looks a lot like the last Wisconsin glaciation. Due to the profligacy of the 1st Apocalypse, there is no fossil fuel left to rewarm the earth to avoid the ice.

Those are the end point apocalypses. Here are some ground rules:

–What’s an apocalypse? It’s a global event that causes massive change, global migration, and the end of civilization as we know it, although not necessarily a return to the stone age. It does NOT cause human extinction. It can be natural (an ice age, megavolcano, asteroid), or manmade (our current Gigafart).

–Apocalypses have dates attached, but they aren’t necessarily instantaneous. The Gigafart will take 1500 years to reach its full ripeness.

–Apocalypses have stories attached. Where does Apophis land, and what happens during the impact and afterwards?

–There’s time between apocalypses, time enough for human cultures to recover. In 525,000 AD, there will be enough history, myth, archeology, and paleontology, for the people of that time to know that 33 apocalypses have happened before them, and that they are facing the 34th. This means that the people living between apocalypses have to leave a traces. What do they leave behind that survives?

–The Rule of Narrative Conservation: people will be recognizably human 525,000 years from now. Yes, that’s a long time in human evolutionary terms, but this is for our personal fun. “Recognizably human” means that future people will be close enough to us that it’s no stretch for writers to write about them and readers to emphasize with them. They’re born, live, love, and die, and have recognizable conflicts. There is no end of history, and there is no point at which people stop being people. It does not mean that people will be the same as they are today, and it especially does not mean that they will have the same races as we do today. Races change over the course of a millennium or two, and 525,000 years is an enormous time for racial change.

–I’m tired of reading about zombies, werewolves, and vampires. If you want a monster pandemic apocalypse, be more original.

–Science rules. Don’t bother with Cthulhu, Godzilla, alien invasions (cf the Fermi Paradox), or fairies coming back. Similarly, don’t bother with nanotech or synthbio disassembler plagues, unless you can explain in detail how the damn things work from a biochemical and energetics point of view. Otherwise, they’re magic fairy dust, and that ain’t science.

Those are the basic rules.

One Prebuttal: The simplest way to come up with 32 apocalypses is to assume that global technological civilization is a destructive bubble that pops. All we have to assume is that it takes about 500 years (on average) for global civilization to grow and collapse, and it takes an average of 15,000 years for the Earth to recover enough to support another global civilization, during which people are stuck living as hunter-gatherers, dirt-scratching farmers, and similar Arcadian folk. This idea has been done by Larry Niven et al (The Mote in God’s Eye) and Charles Stross (Palimpsest). I don’t mind the idea of civilization as a cyclical irruption in history, but you know, I’m really hoping for something more original. Future history as a drunkard’s walk, rather than a wheel of time. What about two or more cycles of history, spiked with various and epic natural disasters? Or are there 32 totally predictable global catastrophes lurking out there? Or some mix of both?

Come play Edward Gorey with the future. If we get 34 separate apocalypses, I’ll put it all together and send it out to everyone who contributed.

Filed under: Colorado Shooting, Real Science Content, Speculation | Tags: Colorado Shooting, Grad school, science

I should be writing a report right now, but that damn shooting at the Dark Knight Rises keeps bothering me, so I thought I’d post my thoughts.

First off, the shooter James Holmes (hereafter Little Jimmy) tried to call himself “the Joker,” and the news media seems to be picking up on this. Quiet, brilliant scientist turns into long wolf monster with no warning! News at 8, noon, 5, and 11! Perhaps I’m cynical, but where I work was close enough to hear the damn news copters orbiting around his parents’ house for hours, and an out-of-town news crew actually stopped us for comment on our way to work out (I told him we were new in town, which wasn’t entirely true).

So let’s demythologize Little Jimmy a bit. Yes, he perpetrated an evil, unjustified act, but in all he was a failure, not a brilliant student and budding scientist, and certainly not the Joker. Let’s run down his record. In fact, let’s really run down his record:

–Bright kid, went to a good high school, got top marks at a good college. Yep, all true, but much as I like UC Riverside (and I know some of the faculty members there), UC Riverside ain’t Harvard. Little Jimmy wasn’t a genius rocketing towards fame and fortune, but just another smart kid.

–Ooh, and he was getting his PhD. True. But Little Jimmy couldn’t land a job out of college, so he went back to grad school. This is a really common move, but evidently the employers didn’t see him as God’s Gift to Neuroscience, for whatever reason. While Colorado is a good school, it ain’t Stanford. Again, this is a smart young man who could have made a decent career, but not a genius.

–He failed to hack grad school, so he quit after a year. Lots of people do this. I’ve known quite a few, including the labmate who committed suicide. It’s a shock to go from being one of the bright undergrads to just another starving grad student, and I suspect it’s getting worse, considering how public schools are getting squeezed by our crazy politics and misguided deans are imposing corporate management models. But I ramble.

Anyway, Little Jimmy may have decided that, since he couldn’t be the next Sigmund Freud, he would try to be the next Charles Manson. So he spends however long acquiring firearms, explosives, body armor, and so forth, and turns his apartment into a discarded set from the second batman film. Do we mention that he calls himself the Joker but dyes his hair orange, not green? Another failure, perhaps.

So he goes on his rampage. What happens?

–His gun jams, thank God. FAIL.

–His major atrocity, the bombs in his apartment, FAILS. Part of this was obviously luck, but…

–He doesn’t die in a blaze of police gunfire. Instead, he surrenders and tells them about the apartment. I hope this was a glimpse of sanity, but who knows? Maybe he wanted to be admired for his evil handiwork.

So yes, he killed at least a dozen people and injured 58 more, destroyed his family’s reputation, and so on, but I do hope that Little Jimmy is remembered as a failure, not as a monster. Based on the presumptive brief glimpse of sanity, I also hope he gets life in prison, and that he grows enough of a conscience to spend the rest of his life regretting his choices.

Was he running amok? In other places, I posted that it certainly looked like it. Now, I’m not quite so sure, but he could have been. For those who don’t know, running amok is a very old phenomenon, Captain Cook, all the way back in 1770, “described the affected individuals as behaving violently without apparent cause and indiscriminately killing or maiming villagers and animals in a frenzied attack. Amok attacks involved an average of 10 victims and ended when the individual was subdued or ‘put down’ by his fellow tribesmen, and frequently killed in the process. According to Malay mythology, running amok was an involuntary behavior caused by the “hantu belian,” or evil tiger spirit entering a person’s body and compelling him or her to behave violently without conscious awareness.” (Source). Not quite what Little Jimmy did, because he planned and prepared for months, but it’s eerie that he dyed his hair orange, not green, and that he killed 12 people, despite having the capacity to kill many times more. Maybe an evil tiger spirit possessed him? It’s as likely as any other post facto explanation pundits are likely to give. Whatever else happened, Little Jimmy was certainly a black swan, and because of that, I distrust any attempts to rationalize his actions.

A rather better idea comes from the August 2012 Wired, in an article called “The Fire Next Time” about how humans mis-process near misses as permission to continue hazardous activities, rather than as warnings to figure out what went wrong and not to repeat it until disaster happens. According to the article, research b the Process Improvement Institute across many industries showed that “there are between 50 and 100 near misses recorded per serious accident, and about 10,000 smaller errors occur during that time.”

Let’s stop blaming the availability of guns, big rifle magazines, the proximity of Columbine near Aurora, or whatever else for Little Jimmy’s atrocity. Instead, let’s look at grad school. I had a rough time in grad school, what with a labmate committing suicide, a conflicted relationship with my advisor, and various chronic injuries that meant I did much of my research in pain. But I didn’t even buy ammunition for the one gun I had, and although I was terribly frustrated and angry many times, sure I was going to fail, I didn’t spend my savings on blowing up anything or killing anyone.

Why not? In my case, the reason was because I couldn’t see anything useful coming from it. I also listened to Garrison Keillor, who can be a wonderful bard about the possibilities of living with failure. And so got on with it, got my PhD and went on.

I’m probably one of those 10,000, someone who could have turned into a monster, had things been a little different in my neurochemistry, my circumstances, or whatever (or whether an evil tiger spirit had noticed me). Possibly I was one of the near misses, people who really should have talked to a counselor, but who worked through their problems without help. Whichever. I do know there are a lot of people like me in grad schools across the country, troubled people who never turn into monsters, who go on to lead productive lives. People who succeed in some fashion, no matter how frustrating the process is.

Little Jimmy Holmes was a failure. People failed to spot the threat he represented, certainly. If nothing else, this might be a wake-up call for grad schools to get a bit more proactive in their students’ social lives (not that I think this will ever happen, but I can dream). Still, even with no intervention whatsoever, only a vanishingly few isolated, angry men of any sort ever turn into monsters. Little Jimmy, for all the deaths and injuries he caused, failed to be as big a monster as he wanted to be, and I’m glad he failed. Good riddance to him.

Instead, let’s praise those who succeeded last Friday, Start with those in the theater who took bullets to protect friends and loved ones, and succeeded, possibly at the cost of their own lives. Let us praise those who helped get others out of the theater, sometimes again getting shot in the process. Let us praise the police who responded quickly, following their training, and caught the murderer. Let us praise all the people who worked for days disarming the apartment. And finally, let us praise all those men and women who get their PhDs in neuroscience and go on to productive careers in many fields. They aren’t the next Sigmund Freuds either, but they are successes. All of them.

Filed under: livable future, Real Science Content, science fiction, Speculation, sustainability, Uncategorized | Tags: grim meathook future, science fiction

I’ve got to admit, starships are intriguing, as is the idea that someone can build a largish skyscraper with a fusion generator in the basement, and that building will contain a village-supporting ecosystem (powered entirely by the fusion generator) and also be missile-proof. On the bad side, this vision seems a bit, I don’t know, silly perhaps? The skyscraper, I mean. That’s effectively what a starship is, though, and existence of one implies the other.

On the other hand, we can assume the obvious answer for the Fermi Paradox, that the reason we haven’t heard from aliens is that starships are logistically impossible, even if they are possible under the laws of physics. This comes about simply because starships require so many breakthroughs in so many fields. A failure to achieve any of these breakthroughs–power plant, shielding, compact, human-supporting biospheres (or stasis, or computer upload systems that last for centuries), and keeping the crew together for the duration of the voyage–dooms the starship. All of them could be impossible.

At this point, some SF aficionados throw up their hands and scream “therefore we’re all doomed! The Earth won’t last forever, and humans have to.” This is foolish. Yes, of course we’re all doomed to die, one way or another (sorry if this is unwelcome news), but Earth has another billion or more years to run before it becomes uninhabitable, and it’s quite likely that humans on Earth have another few million years before we go extinct, no matter how stupid we are.

The basic point here is that humans will almost certainly survive a transition from our current, fossil-fuel based, economy to one that is not based on fossil fuels, and the only reason I say “almost certainly” is because I’m currently reading Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA, and cringing how many attempted suicides the US unknowingly avoided. Anyway, the point is that people will survive, whether we decide to end our dependence on fossil fuels by crashing civilization, or whether we get to innovating and finding ways to do more with less, just as we have for untold centuries.

What will that future look like? In some ways, it will look like the starship future, at least for the next few centuries. As we get nine billion people on the planet, we’re going to have to find ways to feed more people with less land and water. Given how much we currently waste, this may be possible, if not pleasant.

Other predictions:

–Oceanic fishing will largely disappear for centuries. There are so many anoxic zones already that it’s likely that most people will give up fishing, and ships will have to carry all their food with them. I’ve had fun imagining a future Pacific where big, ark-like windjammers travel among the islands, all the food grown or shipped with them and fresh water recycled aboard as much as possible. The islands that survive sea level rise may start to resemble the self-sufficient dome cities of the previous post, since they’ll be less able (or entirely unable) to draw on the sea for their livelihoods. This is a grim thought for those of us who admire the old Polynesian cultures, but fodder for any SF writer who wants to re-imagine the old idea of asteroid belt colonies out in the Pacific, with kite-sailers replacing singleships. Anyone want to mine lava for precious elements?

–Farming will change. We’ll probably start recycling sewage onto farmland (if only to recapture the phosphorus, since we’re running short of mineable sources for that essential element), and we’ll certainly eat less meat. We’re already getting a powerful taste of climate change, with those record-breaking heatwaves and storms, and it’s going to get worse. We’ll have to get used to the idea of crops failing, and we’ll have to get very good at storing food during the good years. Currently, big agribusiness has a lock on both the food economy and politics, but that may fail suddenly, if the few big companies that dominate the Ag industry fail to deal adequately with crop failures, changing climate zones, and other problems. Rural America has been “dumbed down” for most of a century, with the bright kids lured into the cities. We’re facing a time when we need really, really smart farmers. I suspect we’ll get them, and this will affect both agribusiness and politics. Personally, I hope that permaculture takes off in a big way, but that’s because I’m an ecologist and I think it’s cool.

–Politics: It’s amazing how much politics in the US is affected by air conditioners. If the amazingly complicated US power grid starts to fail, people are going to start migrating north, out of current red states and into the blue. Some people say this is what’s driving the current Republican party, and they may be right. America is getting less white, and throughout much of the world, we’re seeing smaller families. There will be a gerontocracy for the rest of our lives, I’m afraid, but after that, who knows? We’re so used to thinking of political economy as growth that it will take innovation to face a future where populations decline.

I could go on, because this is the kind of future that makes more sense to me. Perhaps it’s because I’m a pessimist? Or is it that the idea of human history having millions of years of one damn thing after another is actually more appealing than centuries of adolescent style, unlimited growth? For SF writers, there is good news here:

–there are plenty of Apocalypses to go around. If we really do live for millions of years, we’ll see the end of the fossil fuel age (in the geologic near term), the end of global warming (as I posted on a while back), at least one more ice age, multiple Carrington Events, asteroid strikes, devastating earthquakes and volcanoes, east Kilauea sliding into the sea and inundating the west coast, dogs and cats living together, and so forth. I was toying with the idea of starting an SF scenario called “after the 34th apocalypse” set waaaay far in the future, but I would have had to figure out what all 34 apocalypses would be. The point would be that the end of civilization as we know it might become old hat after a while, with coping strategies and everything.

–Many futures are possible. Given a combination of limited resources and humanity’s incredible capacity for ignorance, boredom, and self-delusion, I predict that people are going to try most options repeatedly. Everything from slaughterhouse dictatorships to drop-out wannabe utopias will appear again and again. Modern giant agribusiness isn’t the first time western civilization tried huge agriculture (see latifundias), and it’s certainly not going to be the last time, although I’m sure we’ll see periods of small farms in the near future. Dictatorships will come and go, and there will always be a new religion popping up somewhere, even if most of them don’t survive much past their creators’ lifespans.

–Science will always be around. It’s common knowledge that most of the world’s current great religions (Christianity, Buddhism, Taoism, Hinduism in its current incarnation, and Islam) were created during the so-called “Axial Age” of empires in Rome, India, and China. They and their descendents are still around, in massively altered form. We’re centuries in to another age of global empires, and I’ve been wondering what new form of religion will come about. The answer was so obvious that I almost missed it: science. History is accretionary, not cyclical. Although Christianity is monotheistic, it early on absorbed a whole body of saints and pagan holidays from the old religions it replaced. Islam and Buddhism did the same thing, and I think the trend is universal among missionary religions. Because of this, I’m pretty sure science won’t go away either, no matter how hard people try to suppress its inconvenient truths. It’s so embedded in all of our lives that, like the notion that God should be capitalized, it’s not going to go away. Science *will* change radically in coming centuries as it subsumes arising cultures, but people will keep doing it. When we go through future ages of upheaval and global empires in coming millennia, our descendents will likely come up with still other “religions” that fundamentally change the way we think. I wonder what they will be?

–Domestication will rule much of the world. As with ants and termites, the human species’ fundamental adaptation has been domestication, which I like to describe as a massive campaign of symbiotic adaptations. While we can live without agriculture, I don’t think we’re going to do so. It’s simply too useful. Rather, I think that evolution is going to continue to take advantage of our domesticated ecosystems, just as it is doing right now. We will see more pests, pathogens, and parasites (including social parasites), and they will only get more sophisticated through coming centuries. I’m quite sure our counter-measures will get more sophisticated too, in a coevolutionary arms race, and I suspect that agriculture in, say, 40,000 years, will look radically different than it looks today. Farm ecosystems will be much more complex, and much of that complexity will be outside human control. Fortunately, I don’t think wilderness will ever entirely vanish, either.

–Similarly, I don’t think machines are going away, and I think that the complexity of mechanized ecosystems will only increase over time. I also think it’s likely that domesticated and mechanical ecosystems will merge more thoroughly than they have already.

In other words, there will be grim meat-hook futures, but I suspect that for every grim meat-hook generation, the next generation will make the best of things, get on with life, and be relatively happy. Things could be worse.

Filed under: Real Science Content, Speculation, sustainability, Uncategorized | Tags: climate change, noosphere

To use the high school tactic, if you haven’t heard of a noosphere before, here is Google’s definition: “A postulated sphere or stage of evolutionary development dominated by consciousness, the mind, and interpersonal relationships (frequently with reference to the writings of Teilhard de Chardin)”

This idea crops up a lot in, well, collegiate dorm thinking, and it generally expounds the idea that the world is evolving in stages from inanimate matter towards some grand future where all thinking beings are connected, there’s universal consciousness, the Singularity has happened, or similar versions on the Christian rapture dressed in scientific terminology (Mssr. de Chardin was a Jesuit Priest, so there is a distinct Christian undertone in this whole idea).

I’m going to argue something very different: the noosphere is already here, it’s been growing for over 500 years, and rather than being a rapture of the nerds, it’s becoming quite a pain in the ass, mostly because the sciences it has fostered resolutely refuse to acknowledge its importance.

This whole train of thought was inspired by a quote from William deBuys’ A Great Aridness (Amazon link). In talking about what we learned from Biosphere II, Mr. DeBuys said, “In this respect, Biosphere II proved a true microcosm of Biosphere I, where venality, ideology, self-interest, and other elements of the globe’s political ecology, much more than the workings of the nonhuman world, have generated the greatest obstacles to solving environmental problems, climate change foremost among them.”

There’s that thumbprint of the noosphere: political ecology. Since I’m not a global climate change denier, I see nothing controversial in de Buys’ statement. The “problem” with it is that it lets slip the dirty laundry. Politics matters. Global politics, a signpost of the noosphere of human thought, is now a major factor in the biosphere. Most biologists and ecologists hate this conception, but most would agree that it is nonetheless true. The ecology of politics is another factor to consider, along with the physical world.

Again, there’s nothing new with this idea. The problem is that most scientists want to keep their science somehow pure. Politics happens, certainly, but arguing that politics is integral to a biological study can cause all sorts of problems in fields where nature is considered to exist separately from human thought.

Of course, the noosphere not new. Once Columbus got back from the Indies, human political ecology has been stitching the world together in radical ways (“reknitting the seams of Pangaea” in Charles Manns’ wonderful formulation in 1493). There are whole ethnicities, such as Hispanics, who are the direct result of political ecology. My ancestors have been living in the US since the 17th Century, and my ancestors come from what are now a dozen European countries. National borders (such as the idiotic Border Wall along the Mexican border) now extirpate species (such as the few Baja rose growing in the US), and the most rapidly evolving plants and animals on the planet arguably are pests and crop plants, both of which depend intimately on rapidly changing, human-maintained ecosystems. Political ecology is important.

More subtly and pervasively, the non-human biosphere is dominated by human politics and thought, whether its our effluents causing climate change (“Global Wierding” in deBuys aptformulation), fishing and hunting radically changing ecosystems throughout the world, park boundaries (which turn what used to be huge gradients across which organisms spread into discrete island patches), even concepts of nature which ignore nature outside those park boundaries and guide our actions to favor some species and harm others.

I could go on, and in fact I think it might make a nice book at some point. The problem is that this is a dirty, unromantic conception of the noosphere, one that brings along all the destructive baggage that most of us got into ecology to avoid. It also conflicts with de Chardin’s arguably romantic conception of progress from inanimate nature to a God of pure consciousness. Consciousness (in its human incarnation) is a part of the biosphere now, but the biggest factors right now aren’t our lofty, enlightened thoughts, but rather our worst impulses: “venality, ideology, self-interest, and other elements…”

This is in line with real evolution. While mass extinctions happen (one has been happening for the last 50,000 years or so) major lineages seldom go completely extinct. We add on, rather than proceeding from stage to stage. We’ve still got theropod dinosaurs around (birds), and they’re arguably more common than they used to be. Mammals are an ancient lineage that predates the dinosaurs, and we’re here. So are reptiles and amphibians, along with insects, fish, and so forth. And as Stephen Jay Gould once noted, rather than living in an Age of Mammals, we’re living in an Age of Bacteria, as we have for the last 4.5 billion years. They keep the critical recycling bits of the biosphere working, just as they always have.

What’s wrong is de Chardin’s concept. He saw evolution as progress in stages, from inanimate rock through bacteria, plants, invertebrates, reptiles, mammals, man, then the Noosphere (with celestial, uplifting music, no less). Evolution is more like a compost pile, with new stuff added, often by chance, at irregular intervals, and a pile that continues to churn nonetheless.

So yes, welcome to the noosphere. We were all born here, but we never realized it, did we?

This is a quick thought, prompted by reading about the purported “self-domestication” of bonobos (article link). The idea is that bonobos are the highly-sexed, peace-loving apes that they are because, unlike chimpanzees, they didn’t have to compete with gorillas for food. They lived south of the Congo River, in an area isolated by drought, where gorillas couldn’t survive. Freed of the brutish struggle for existence, they dropped many of the competitive behaviors that chimps display, and became more matriarchal, more prone to negotiate than lash out. In other words, they started acting more like domestic animals. They self-domesticated.

Or so the hypothesis holds. I suspect there are a number of problems with this, starting with reports that wild bonobos don’t act quite the same as captive ones, but whatever. Let’s assume for a moment that this idea is right, that some species “self-domesticate” by becoming more social and cooperative. Let’s also assume that modern humans are one of the self-domesticating species. Perhaps we’re the bonobos to Neanderthal chimps? Except for the inconvenient fact that there were at least two if not four other species of hominids around at that time, the analogy is seductive.

What caught my attention was an idea from Judith Stamps, a professor emeritus at UC Davis, that self-domestication might be favored on islands. That got me thinking, because I’ve had a bit of experience on islands.

Islands have some classic problems: island animals don’t fear humans or introduced predators. Insular plants lack the defensive compounds of their mainland relatives. When mainland animals and plants get to islands, chaos typically ensues, and as a result, island species are disproportionally represented on endangered species lists. The classic explanation is that in the absence of predation, island organisms evolve to stop wasting their resources on defense, and instead pour those resources into living. Or, as I put it, instead of living in the South Central mainland, with the bars on the windows and the guns by the bed, the island species live on the insular West Side, where they compete through finances, conspicuous consumption, and social displays, and investing in financial instruments instead of home defenses.

Now look at these characteristics again. Island animals are tame. Island plants are highly edible, often with bigger leaves and blander fruits. Does this remind you of anything? It should. It sounds like a farm or a garden.

Perhaps domestication is more about turning farms and gardens into islands, and this habitat, as much as selective breeding, selects for the species that can survive on those islands. Yes, of course humans are the primary environmental filter, and species that don’t play well with humans get voted off our islands every time we weed. Yes, we routinely breed and select for organisms with the traits we like. Still, maybe domestication is less about selective breeding, and more about habitat manipulation. When we made habitats for humans through gardening, we created a myriad of islands for evolution to work on.

Perhaps Insularizaion causes self-domestication. Bonobos may have self-domesticated in a forest island on the south side of the Congo River. Modern humans may have self-domesticated on the coast of southwest Africa some 80,000 years ago, when the population geneticists say that our species almost went extinct. Being stuck on a small island of favorable habitat might have helped us evolve more sophisticated social cognition, something that later served us well, when more favorable climates let us spread across the world. Perhaps all episodes of domestication (or self-domestication) happened this way. It’s a testable hypothesis, more or less.

Now, our islands of agriculture have spread across the world, becoming a major biome in their own right, and our defenseless crop species, as tame as any island species, are everywhere. One irony of this situation is that wildlands are more and more becoming islands. We may see self-domestication in some of the remaining wildlife, if our society doesn’t collapse first. This is a big concern among land managers, who are now attempting to maintain connections among reserves, but many urban parks are already isolated. Will park plants and animals lose their defenses? We’ll see.

The other irony is that the sheer expanse of domesticated landscapes now favors the evolution of species that can take advantage of these resources, species we call weeds, pests, and pathogens. Things that don’t need to play well with others in a limited space, because space is no longer so limited. These evolving super-pests are de-domesticating themselves, abetted by our efforts to control them.

We may be in for interesting times ahead, with rewilding farms and self-domesticating parklands. Nice to know that the future will be interesting, in the proverbial sense.

This is too good not to share. I’ve been reading Robb Dunn’s six-part blog series on Civilization, fungi, and alcohol, and they are certainly inspiration.

Before I go further, here are links to

One (A Sip for the Ancestors: The True Story of Civilization’s Stumbling Debt to Beer and Fungus)

Two (Fruit Flies Use Alcohol to Self-Medicate, but Feel Bad about it Afterwards)

Three (Strong Medicine: Drinking Wine and Beer Can Help Save You from Cholera, Montezuma’s Revenge, E. Coli and Ulcers)

Four (By looking carefully, Japanese scientist discovers the secrets of termite balls)

Five (Five Kinds of Fungus Discovered to Be Capable of Farming Animals!)

Six (Exhausted Writer Discovers First Cave Painting of Yeast)

As a jack mycologist, I have a fondness for heartwarming stories about how fungi have domesticated humans to make life easier for them. Oh, wait a minute, how humans use fungi. Right…

Anyway, Dunn’s writing includes an essay about how humans may have domesticated grains not to make bread or gruel, but to make beer. He also writes about how fruit flies self-medicate with alcohol (apparently, the parasitoid wasps growing inside them die from alcohol intoxication faster at alcohol concentrations that only leave the flies moderately impaired, and infected flies preferentially head for the hooch at the first chance they get), and then writes about how humans may do the same thing, at least inadvertently.

We’re venturing into GI illness and cholera here. Hope you weren’t drinking anything non-alcoholic while you’re reading this. If you need a drink, I’ll wait. Ready? Apparently, drinks like tequila, beer, and gin, and less often wine and ethanol, can kill bacteria like the ones that give us cholera, listeriosis, and so forth. With cholera, adding gin to contaminated river water will eventually kill the cholera (note the eventually–it’s not instantaneous), and beer seems to have similar properties. Neat stuff, if you’re trying to understand why some people died in pre-modern cholera epidemics, while others survived. Maybe, like fruit flies, humans feel better when they drink not just because of the alcohol buzz, but because the alcohol has taken out a bunch of pathogens. This is a nice concept, especially considering what some of us ate during college.

At the end of the third section, Dunn postulates that the European Age of Exploration might not have happened without beer, wine, and so forth, because they carried huge supplies of these drinks on board to keep the sailors thirsts quenched. Columbus’ ship may have been half beer by weight, for example.

That’s a fascinating hypothesis. At first glance, it seems plausible. After all, we didn’t have Indians sailing east to colonize Europe, even though the Altantic currents favored them. Maybe it was because they didn’t get drunk enough. Maybe the key to conquering the world is to get on a booze cruise with a bunch of your germy buddies, and load up more beer than weapons or trade goods.

I thought about it some more, and realized that we have the beginnings of a replicated historical experiment here. After all, the Europeans may have been the booziest, but they were scarcely the only long-distance sailors out there. We’ve got the Chinese, the Arabs, and the Polynesians (and to a lesser extent, the Micronesians) all cruising the deep ocean. Muslims allegedly don’t drink (although I do like Shiraz wine, first created in Iran, and alcohol is an Arabic word…), Chinese do drink, but they typically have less alcohol dehydrogenase in their bodies to break down alcohol than do Europeans (not that this stops them), and the Polynesians didn’t brew alcohol at all, although the Micronesians did regularly brew coconut toddy. Then again, the Polynesians weren’t sailing into pestilence ridden cities, they were exploring untouched islands. Hmmm. Who got the furthest in world domination? Back before 2000, I mean. That’s why there may be an experiment here.

Is there a link between the willingness to sail with a lot of alcohol and the ability to colonize the world? I’m not sure, primarily because I don’t know how much alcohol Arabs and Chinese carried on their ships. If those data are available, we’ve got an alternative hypothesis to Guns, Germs, and Steel here. Did Europeans sweep the globe because we were willing to drink more beer than anyone else? I don’t know, but it might just be testable.

Now that we’re becoming a group of effete caffeine addicts, it appears that the rest of the world is catching up with us. I do hope that’s a coincidence.

For the science fiction writers, does that mean that our hypothetical generation ships will only fly with alcohol aboard? Will Buzz Lightyear be more than a cartoon character someday? The possibilities are endless.

Sad news today. Two grand ladies who had a strong influence on me have passed away. I can’t say that I knew them, although I heard both of them speak.

Anne McCaffrey died at her home in Ireland. She is, of course, known for her Pern novels, and I didn’t realize until I saw her obituary that The White Dragon was the first science fiction novel to make it onto the New York Times bestseller list.

Lynn Margulis, winner of the National Medal of Science, died at her home in Massachusetts. She’s best known for demonstrating that eukaryotic cells derived from serial endosymbiosis, the fusing of several prokaryotic cells to form the organelles of the eukaryote (and yes, I’m keeping it simple). I don’t think she was the first person to consider this idea, but she certainly was the one who demonstrated it and popularized the concept.

A copy of Dragonflight was the first book I ever had autographed, and I still have it. As a child in a house with a cat named Smaug, you can guess that I ran into dragons early, but I was drawing Michael Whelan-style dragons as soon as I saw the cover of The White Dragon in my parents’ hands. I’ve had a fondness for dragons ever since.

As for Dr. Margulis, she and I both went to the same school, albeit decades apart, and her books (particularly The First Four Billion Years, which I read for fun as an undergrad) introduced me to the concept of symbiosis, something which ultimately became the topic of my PhD research.

Oddly enough, the first book I wrote, Scion of the Zodiac, is in part about symbiosis, and in part about dragons. Thinking about it, perhaps I should have dedicated it to the two of them.

The world is a better place from their lives and their work, and they will be missed.

Filed under: Real Science Content, science fiction, Speculation, Worldbuilding | Tags: interstellar colonization, science, science fiction, worldbuilding

Let’s assume, for the moment, that interstellar travel is possible. Let’s further assume that there’s no magic wand of teleportation or FTL, traveling to another star takes a looong time, and it basically means colonizing your starship (or gaiaspore, if starship is too passe for you). The ship may be Charlie Stross’s hollowed out asteroid, or a comet, or something similarly large, but whatever the ship looks like, the basic idea is that people don’t put their lives on hold for the duration of the trip. Rather, they settle into their ship, and then they (or their distant descendents) settle another world elsewhere.

The two-step is an environmental filter. Many technologies that are ubiquitous on Earth, such as cooking knives or internal combustion engines, are non-starters in free fall (where scissors work better) or in small biospheres (gasoline engines). Consequently, interstellar travelers will abandon quite a lot of Earth’s technology when they live in space. They’ll also certainly invent lots of uses for vacuum and all sorts of high energy particles, but that’s another story.

Anyway, once they’ve made the first step of abandoning Earth tech and its associated culture (no car culture in space), once they get to another planet, they’re faced with a new environment where they have to adapt again. Suddenly they have dependable gravity and a huge biosphere to draw on (or at least, a planet’s worth of resources). In the second step, do they simply adapt spacer culture and technology to meet the challenges of the new place, or do they read through copies of the ancient Wikipedia and start experimenting with, say, gasoline engines again?

There’s a real-life analogy to this process: Polynesia. As the Lapita peoples settled the Pacific, they abandoned things like pottery, weaving, and flaking rock (and possibly bronze metallurgy) as part of their adaptation to living on coral atolls. Once they colonized places like New Zealand, they didn’t spontaneously pick up their ancestor’s technologies, even though they had the resources (such as clay) to do them again. Instead, they adapted their Polynesian tool kits to new surroundings.

There are some subtleties here: for example, Polynesians didn’t just abandon pots because there was no clay on atolls. They were abandoning them before they got to the atolls, because they were switching from cooking over an open fire (where pots are useful) to cooking in an earth oven (where pots are useless). Moreover pots are more fragile than wooden bowls, coconut shells, and gourds. Similarly, they switched from flaking rock edges (on obsidian) to grinding, because grinding works on all sorts of materials, including the giant clam shells used for adze blades on atolls, while flaking just works on glassy rocks. The thing is, adzes work better when they’re ground rather than flaked (whatever they’re made of), the Polynesians also had bamboo (which can be shaped with an adze to make a nice sharp knife), and Easter Islanders figured out how to flake knives on their own in any case. The bottom line is that loss of technology isn’t just about losing the tech, its involves a whole shift to other tools and practices that sometimes makes things superfluous. A society on electric cars won’t be exactly the same as a society built around gasoline cars, because the two vehicles have different strengths and weaknesses.

Getting back to the interstellar two-step, it’s a fun to play as a thought game. If you were leaving Earth for space, what would you abandon? If you were planning on getting your descendents to settle elsewhere, would you have them do: resurrect Earth culture, adapt spacer culture, or both?

Examples of adapting spacer culture might range from using scissors and shears in place of knives, to using air guns instead of gunpowder, to using various cooking techniques that work regardless of gravity, but not gravity-requiring methods such as frying. How about transportation? Art? Agriculture? For example, if they kept goats in space, would you have them bring along cow embryos and the means to grow them to re-establish cattle, or would you rather give them the biotechnology to engineer a giant goat that fulfills most of the cow’s roles in terrestrial agriculture?

What do you think? How would you do the Interstellar Two-Step? I’ll say right off that there’s no right answer. This is a thought game, pure and simple.

Just realized that I should have posted this for Halloween. So instead I suggest using this to start (or end) conversations on Thanksgiving.

Years ago, I came up with a way to objectively test astrology and personal horoscopes. It’s simple, and any experimenter can do it if he or she can find a bunch of willing participants and convince them to spend a few hours rating a bunch of horoscopes. I’ve described my results below, and I encourage other people to try it, as a psych experiment or just for fun.

Experimental Design:

Hypothesis: If astrology is useful, then a person’s horoscope should apply to them more than someone else’s horoscope does. Here, I’m not interested in any purported celestial mechanisms. If a horoscope works as advertised, then a personal horoscope should be more relevant to that person than someone else’s is (or a randomly created horoscope). If this is the case, then it’s worth looking for a mechanism. If the null hypothesis in the next paragraph is right, then there’s no point in looking for a mechanism, is there?

Null hypothesis: subjects will either rate all horoscopes approximately the same, and/or most subjects will find other people’s horoscopes more relevant to their lives than they do their own. I’ll explain why this might be the case lower down.

Method:

1. Find a website that gives out free, nine planet, twelve house horoscopes.

2. Recruit a bunch of experimental subjects. I’d suggest 10, and fewer than five is problematic. Get their birthplace, birth date and birth time information.

3. Compile everyone’s horoscope from the same website. The experimenter should strip out any identifying information (for example, anything that says Libra, Virgo, etc), and the subjects should not see their horoscopes prior to the experiment. Typically horoscopes are printed as a list of paragraph statements, one for each planet and house.

4. If you want, you can even add in randomly generated horoscopes.

5. If you want to make it simpler, you can do one more step. People who were born in the same year tend to have some of the same planets and houses (particularly for the outer planets, which move very slowly). To make it easier for the subjects, you can compile all the paragraphs into one long paper, and have everyone rate every paragraph once. You will have to create a key for which paragraph goes with which horoscope to compile the stats, but this saves on work for the subjects.

6. Have everyone rate EVERY horoscope, every paragraph, on whether that paragraph applies to them or not (I suggest: 1 pt if the paragraph is relevant to the subject’s life, 0 if it’s neutral, -1 if the paragraph does not apply to the subject’s life).

ANALYSIS:

7. Compile every person’s scoring of all horoscope paragraphs. Add up the scores per horoscope.

8. If astrology is true, the prediction is that each person should have scored their own horoscope higher than they scored those of the other participants. The stats for this are a bit more complicated than ranking individual scores, because just by chance, you would expect some people to pick their own horoscopes as the most applicable. Still, it’s not hard, and if the stats look too ugly, simply post how people rated their own and other horoscopes.

9. Collect post-test impressions from the subjects, distribute the results, and have fun talking about it.

When I ran this with 6 subjects with four additional random horoscopes, I got equivocal results (1 person picked their own horoscope, 5 people chose other people’s horoscopes, but with the small sample size, I couldn’t test the hypothesis). I’d love to see other people replicate the test and post their results.

The nice part about this is that it gets around all the tired ideological debates (“it’s not science” vs. “keep an open mind”) and looks at whether printed horoscopes have any perceived relevance to the people who requested them.

What I learned about horoscopes is that, when you read your own horoscope, you tend to focus on the bits that are relevant and ignore the rest. Horoscopes are written to favor this habit: they have a bunch of generally applicable advice mixed very nicely together, much like Forrest Gump’s box of chocolates. However, when you read other people’s horoscopes, what you find is that their horoscopes are also applicable to you. In fact, you may well like someone else’s horoscope better than you like your own. Five of the six people above found that, and one person even preferred a randomly generated horoscope over his own.

Most divination methods work this way: it’s not what is displayed by the cards, planets, coins, whatever, it’s what the person reads into them. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but I think it is better to understand how such a method works, rather than uncritically accept it.

Try it out, and tell me what you think.