Filed under: livable future, Real Science Content, science fiction, Speculation, sustainability, Uncategorized | Tags: future, green, sustainability

This one’s inspired by this NPR story, about sustainability.

What does sustainability look like? In The Ghosts of Deep Time, I have one character say that civilization is cool, quiet, and green, and that’s still my thumbnail for a sustainable city. To unpack that a bit:

Cool. Forests are cooler than grasslands, not because they get less sunshine, but because they catch more of that sunlight and do things with it. Scientists can actually determine how stressed a forest is by measuring how hot it is. Efficiency translates into less energy loss, which means less heating.

In cities, we tend to waste a lot of energy, which is why they are hot. Most of the sunshine gets reflected, or absorbed into surfaces that it heats up. Most of our equipment runs hot, which means we have to get rid of that heat too. A sustainable civilization doesn’t waste much energy, so it’s going to be cool.

Quiet goes with cool. Much of the noise of modern civilization is wasted energy, gone to making sound waves instead of useful work. An efficient civilization is going to be quiet as well as cool.

Green. This is both in philosophy and color. Plants can perform a large number of functions, from cleaning water to providing shade and cooling air. Moreover, we humans aren’t so far from our evolutionary roots that we don’ enjoy having plants around, even if our thumbs are scummy black rather than green. Obviously, a sustainable city will be ethically green as well, but from a simple design standpoint, I think it’s difficult to have a sustainable city without having a lot of functional plants around.

Anything else? Or can we do without one of these?

Filed under: livable future, Real Science Content, science fiction, Speculation, Worldbuilding | Tags: science fiction, starships, sustainability

On Charlie Stross’ blog, I think I called starships gaiaspores, because apparently the term “starship” is passe among the cognoscenti. Or something like that. Gaiaspore does have a certain endearing clunkiness, so use it if you wish. I’m mostly calling them starships here.

But I’m thinking about something a bit different. What comes before the starship? If you remember James Burke’s Connections from the late 1970s, you remember that no invention comes about without a long chain of preliminary discoveries. For living in space, we’re going to need a lot of precursors. What are they?

Let’s start science fiction: how do others see us getting to the stars? The science fiction answers range from, well what we have now (Scalzi’s Old Man’s War, where Ohio hadn’t changed at all in 200 years, except that the elderly now emigrate to the stars) to planetary destruction (Octavia Butler’s Xenogenesis trilogy, where the living, moon-sized spaceships basically ate planets down to the mantle before departing). Charlie Stross seems to break on the large side of the spectrum, talking about hollowing out asteroids and putting slow motors on them. That would require us to digest a few large cities, at the very least.

Assuming a starship is even feasible, it’s going to demand some things we’re currently really bad at, like living at close quarters with nuclear or fusion plants, living sustainably, and living in free fall or microgravity. No culture on Earth lives this way now (although people try it for a few years as an experiment).

So culturally, how do we get there from here? Cultural evolution tends to be path dependent, so it’s not as simple as re-educating the people we have. Imagine turning a Tea Partier into an 18th Century Japanese farmer, or a Papuan highland farmer (both picked because they lived fairly sustainably), and you’ll see the problem. Because of the path dependence, it’s fun to think about where we need to be going before our culture evolves to the point where it can live in space.

What do you think? What do the predecessors to the stars look like? Remember that a pre-starfaring culture has to work on its own merits. Like a bird ancestor, it can’t “half fly.” Those too-small wings have to perfectly good for something else first.

When I wrote Scion of the Zodiac, I cheated on this question. I assumed that we’re going into a post-oil dark age first, and that somehow in that unrecorded time (heh heh) we learned the critical lessons of sustainability that allowed us to go to the stars after the next Renaissance (spurred, I think, by discovering a readable copy of Wikipedia and translating it. No sarcasm there). However, I’ll admit that I was more interested in low tech terraforming than star flight, so I spent more time figuring out how you could survive in an alien biosphere at a low tech level. That last stipulation was so that I couldn’t use magic tech boxes to make life livable. For my “barefoot gaiaformers,” I used three books as my primary references: Bill Mollison’s An Introduction to Permaculture, Jim Corbett’s Goatwalking, and Paul Stamets’ Mycelium Running. Those three books are ones I’d recommend for any post-oil bookshelf, but there’s a lot of good material in there for how to run a gaiaspore. Note that none of these books are mainstream, which is why I think path dependence matters. As for the mechanical side, I’m only starting to think about it.

Obviously, I can babble about this for hours. But what do you think? Can we get to the stars from here? If so, how do we make the connections, and what do the intermediate culture(s) look like? If not, what’s standing in our way?

Darren Naish wasted a lot of my time in the last two weeks, not that it was his fault. It was fun, actually. I was looking for a distraction, and I found it in his discussion of protobats. I didn’t (and don’t) believe the model he put up there, because it doesn’t make sense. At one end, there’s a nice, tree shrewish gliding animal, and at the other end is a bat, and in the middle is a flying insectivore with big hands. What happens in between?

• It goes from rear-wheel drive to front-wheel drive, which is another way of saying that the antebat (bat ancestor with no aerial modifications) has the strong hindlimbs, flexible spine, and barely rotating shoulders common in mammalian quadrupeds, while bats have enormously strong and flexible shoulders, highly reduced pelvises, and hip joints that have rotated substantially, such that their knees tend to point outwards or even backwards. The protobat (something with a patagium and presumably some aerial ability) would be a mosaic in the middle.

• It goes from a rigid glider to a powered flapper. I think I saw this problem first mentioned in Grzimek’s Encyclopedia, but I’m probably wrong, and it was a decades ago. The problem that someone pointed out is that a flapping flying squirrel doesn’t glide farther, it falls out of the sky, for two different reasons.

–First, there’s the question of how a flailing patagium generates lift, especially when the trailing edge is being held semi-rigid by the hind legs. It will lose lift because the aerofoil is disrupted, and it is unlikely that the forelimb movement will get air under the patagium any faster.

–Second, gliders tend to have fairly long bodies, with the center of mass in the center. Increasing strength in the arms pulls the center of mass forwards. You can replicate the problem by making a wide-winged paper airplane and adding paperclip or staple weights, and seeing what this does to the plane’s flight characteristics.

Worst, the hypothetical protobat does makes all these structural changes while needing to glide. If I was feeling snarky, I’d point out that this is akin to evolving a helicopter from a glider, and it’s certainly evolving an ornithopter from a glider.

The real problem with these ideas is that the intermediate stages look less able than their predecessors. This seems to violate evolutionary theory, which posits that evolution proceeds blindly, favoring traits that increase (or at least maintain) fitness, traits which will spread through a polymorphic population and eventually take over, possibly through isolation. A flapping, mid-weighted flying tree shrew seems to embody the worst of both worlds, since it doesn’t have the advantages of flight, nor does it have the simple stability of a glider.

So I started thinking. If bats didn’t evolve from something that looked like a tree shrew, how did they evolve? I assume that there are two limits:

1. There are no extant protobats. This supports two ideas. It implies that evolutionary theory is correct. If bats were at a selective disadvantage, there would be lots of non-flying chiropterans around. It probably also implies that protobats had an advantage over antebats as well.

2. We’re pretty sure that bats evolved in the Palaeocene, simply because their fossils show up in the early Eocene. That tells us a bit about the environment in which they evolved. For simplicity, I’m going to say that it looks something like modern Papua New Guinea (there’s a bit of research behind this statement, but it’s not germane. Take it on faith for now).

Designing an antebat

It’s probably instinctive for biologists to think of gliders as the antecedents to powered flyers, but this may be problematic. There are quite a few extant gliders, for example, but how many of them launch with their front limbs? The only group I could find are the freshwater hatchetfish, and as noted in the comments on Naish’s blog, they are jumpers, not properly gliders. However, all flying animals use their forward limbs to propel themselves through the air. To me, this suggests that we may mislead ourselves by assuming that the ancestor of a flying animal looked like a flying squirrel.

What other way is there? Let’s look at bats and bat development. I don’t for a second buy that bat ontogeny exactly recapitulates bat phylogeny, for the simple reason that it doesn’t in humans. Enormous wings need to develop first and fastest, just to function. That said, the developing bat fetus does suggest a few possibilities.

First, their wings are very different than the hind feet. This seems obvious, but one possibility is that protobats looked like the so-called flying frog ( such as Rhacophorus nigropalmatus) where all for feet are enlarged. There’s no evidence for this in bats: their hind feet are much more similar among species than their wings are, and I assume that this has always been true. Antebat hind feet probably look like those of extant bats. Perhaps their front feet looked like those hindfeet as well.

Second, it appears that the bat’s pelvis is splayed even in the embryo. People seem to assume that the bat pelvis splayed to accommodate the growing wing, but there’s no particular reason to think that.

Third, modern bats have a massive amount of morphological diversity in their heads, but that has as much to do with echolocation as anything else. Still, I think it’s reasonable to assume that antebats had a reasonable amount of head diversity, to the extent that different species or morphs may have consumed arthropods, nectar, fruits, and tree gums, much as modern bats do.

So what did I come up with?

Arachnosorex dubius: a hypothetical antebat

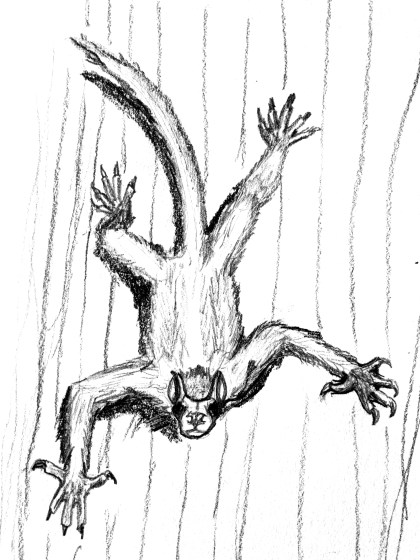

Yes, that’s the dubious spider-shrew, and I’ll be amazed if they ever find it. The name describes both how I think it moved and the niche it held. The images above are my crude sketches of the critter.

In constructing this antebat, I started backwards. What if, rather than the patagium coming first, the hip and shoulder alterations came first?

Are there any animals that have powerful front shoulders and outward pointing knees, and second, are there any advantages to this configuration? Bats have these characteristics, (as do spiders and other non-mammalian animals). Many bats are quite good on vertical surfaces, even ceilings, and they cling well. Something like a vampire (Desmodus rotundus) moves well on the ground, on walls, even on rough roofs, and can launch itself into the air using the power of its forelimbs. The advantage of those backwards pointing hind feet is that they make excellent grappling hooks. An antebat with strong forelimbs and backwards pointed hindlimbs would be quite agile on a variety of surfaces, whether face up, face down, or sideways. However, it gives up some speed for this maneuverability (since it gives up that characteristic mammalian gait, the gallop), so the antebat would be limited to areas like tree-trunks (on the bark or inside a hollow tree), on thin branches (especially the underside of branches) and in caves—in other words, places we find bats now.

This satisfies the first criterion, that bats outcompeted their predecessors. Here I’m suggesting that antebats exploited the same types of food sources as bats do now. Since bats are faster (through flying) than antebats, bats also have a comparative advantage. Additionally, these types of habitats were available in the Paleocene, so it satisfies the second criterion

From nose to tail: the spider-shrew’s head is based on a primitive fruitbat, with a smaller braincase but still well-developed eyes. The forelimbs are well developed, but there is little enlargement of the hand. The hindlimbs are splayed, and the spider shrew overall has a semi-sprawling posture. However, it can move effectively on the ground. The tail is thin and fairly stiff. Its primary function is to act as a support when the antebat is climbing.

Instillator hypotheticus: the dropper, a hypothetical protobat

This “hypothetical dropper” was inspired by a fruitbat photo I found on Flickr. In this case, the patagium is developed, but I see no reason why it should have a hairless patagium.

Here I suggest that antebats became protobats by developing long-distance jumping and falling as an efficient defense and as a way of covering long distances. This lifestyle change hinged on developing more powerful forelimbs and better vision (echolocation evolved after bats flew, according to the fossils). While yes, I’m suggesting a gliding intermediate, in this case, I think it’s likely that protobats powered their takeoff jumps with their forelimbs, not their hindlimbs. They saved on weight by making their bodies more compact and their limbs longer, as seen in modern bats. Probably finger elongation started initially as a way of increasing patagium area (as here, with the dropper), and protobats early on developed the folded wrist we see in modern bats, effectively climbing on the backs of their wrists, with their thumb claws providing the support of the five claws of the antebats. It’s also possible that the uropatagium developed with the arm membrane, giving a “three-winged” form to glide with before ultimately developing into the bats we know today. The advantage of the three-winged form is that there is a separate wing structure that, combined with the highly developed shoulders the protobat inherited from its antebat ancestors, can lead to ultimately to powered flight. The more Instillator develops its forelimbs, the better it does.

Diet wise, I suggest no change from antebats to protobats. The protobats ate the same food as their ancestors did and their descendents will. As with the spider shrew, this satisfies both limiting criteria.

Filed under: pseudonyms, Real Science Content, Speculation, Worldbuilding, writing

So now I’m not content with the Paleocene, and I want to deal with the lower Cretaceous?

Actually, this comes from a blog discussion I got sucked into on at SVPOW, on a really interesting Sauropod reconstruction by Brian Engh. As I noted over there, I’m posting some first thoughts on dinosaur-plant interactions over here.

For fun, I’ve been writing a time travel story set in the Paleocene, and so I’ve gotten interested in the weirdness one runs into going back in time. It’s another facet of worldbuilding, except that, instead of setting it on an alien planet far, far away, I’m trying to figure out the deep past.

The central problem is, I think, one of modern perceptions. To demonstrate, I’m going to choose three very different ecosystems: redwood forest, Midwestern prairie, and California needlegrass grassland. The redwoods have been around for a *very long* time, and even into the Paleocene, they were dominant in a lot of places, with ferns growing in the open fields around them (grasses didn’t really show up until the Oligocene, if I remember correctly). Most people’s view of the redwoods is this quiet place where the biomass is 99.9% plant and the herbivores are mostly absent. Fire is mostly absent too: they call the redwoods “the asbestos forest” for good reason.

Contrast the redwoods with the prairie, where the interaction between grasses and grazers pretty much dominates the system. Prairie grasses tolerate grazing and fire, usually much better than other plants tolerate grazing and fire. But it’s really about grazing, and when you remove the grazers, it’s hard to keep the woody plants from taking over. It’s a neat trick: everything gets eaten, but the grasses simply regrow better.

Contrast both with the California grasslands, where there were few (if any) grazers for the last 10,000 years or so. California native grasses are horrible at tolerating grazing. They can be mowed once per year, and that only about 1ft. off the ground. More mowing than that, and they die. But they tolerate fire just fine.

Getting back to the sauropods, I criticized Brian’s reconstruction of the great beasts knocking down the forest, and he (quite properly) took exception. But to me it is a paradox: why would there be a coniferous forest there at all? All those enormous dinosaurs, which ranged from the size of hippos to medium-sized whales, were living on a diet of conifers, possibly ferns, and possibly cycads and cycadeoids. If you think about this for a while, you realize how very bizarre it sounds. From the fossil evidence, it appears that conifers and ferns are good food, and that doesn’t make a lot of sense. Sure, deer go after arborvitae and yews, but they kill the conifers. And ferns are full of fascinating carcinogens, while cycads are possibly even more nasty and tough. And very slow growing. If animals don’t routinely eat conifers and ferns today, why were the biggest land animals of all time chowing down on them 24/7 a hundred million years ago?

So, how do you grow a sauropod on such a crappy diet? The best answer I can come up with is that, back in the Mesozoic, there must have been another guild of plants around. These were conifers and ferns (if not cycads and gnetales) that used the prairie grass trick. They tolerated browsing, because it killed off their competitors and they could regrow. With the dinosaurs extinct, the plants collectively switched to a strategy of repelling smaller herbivores (mammals and insects), just as the native grassland species did in California. This is the Paleocene environment I’ve been researching, and we still see it in places like Papua New Guinea.

What did the mesozoic browsed conifers look like? That’s another problem I’m having. I don’t know of a modern conifer that tolerates browsing well. However, there were lots of extinct conifers back then. Ferns too. Still, I’m guessing that the Mesozoic forests had more in common with prairies than they do with the redwood cathedrals of today. They were heavily browsed, and seedlings probably recruited in meso-sites where the dinosaurs couldn’t eat them. They probably also root-sprouted readily, just as modern redwoods do.

As for size, I suspect that the tallest mesozoic conifers simply overtopped even the giant sauropods. But I don’t think they got as big as do modern trees, because of the respiration problem. Plants respire just as animals do, and plant respiration rates depend on temperature. There’s a reason that the really big trees grow where it’s cool and wet. It’s easy for them to generate a huge carbon surplus for wood in an environment like that, and the wet weather and fog helps them maintain the positive water balance to keep the tree tops hydrated. A tree in a hot, dry environment simply can’t grow that big, because it has less surplus carbon to put into wood (more carbon went into feeding hot cells), and there is less water to feed the high branches. As I understand it, the Jurassic was (on average) hotter and drier than today, so I’d guess that Jurassic conifers weren’t the giants we see today. And while some of them could overtop even Sauroposeidon, I suspect that many had to live out their lives in the browsing zone, forming some sort of weird multilayered conifer fern multiprairie/savanna.

Long, rambling post, and I’d welcome your thoughts. As I noted above, I’m ultimately interested in trying to get my head around what the Cretaceous looked like. The Paleocene I understand to some degree, but the Mesozoic is a new world to me, and a very strange one. It’s fun to figure out how to do justice to it properly in art or literature.