Filed under: Uncategorized

I’ve been having a lot of fun reading Curt Stager’s book Deep Future: The Next 100,000 Years of Life on Earth, (Amazon Link), and I highly recommend it, especially for anyone interested in science fiction. I linked Dr. Stager’s webpage to his name up there, but for anyone who doesn’t want to follow the link, he’s a PhD paleoecologist, as well as a science writer. In other words, he knows what he’s talking about.

The reason for highlighting his book here is what he lays out for the future of atmospheric carbon on this planet. I think the people who glance at this blog get the idea that I’m not a typical science fiction geek. I’m getting increasingly less fond of the miracle fix, which in this case would be something like fusion (“safe,” “cheap” energy), plus a miraculous gadget to turn CO2 back into a coal that doesn’t involve burying a swamp under rock for a few dozen million years. Also, I’m a SFF maverick who doesn’t really believe that humans will a) go extinct in the near future, or b) transcend through some singularity to the point we are no longer human. That was me ten years ago. Now? Not so much.

The question is, what does the next 100,000 years hold in store for us? Oddly enough, it does depend on how much carbon we burn in the next century or so, whether we go for the conservative 1000 gigaton release of CO2, or the “use up all the coal and to hell with it” 5000 gigaton release of CO2. These are the “moderate” and “extreme” scenarios used by the International Panel on Climate Change, incidentally. To put it into perspective, we’ve released something like 300 gigtons of CO2 since the start of the Industrial Revolution, so the IPCC’s idea of moderation is pretty grimly realistic, compared with the 350 ppm goals of climate activists (the idea is that 1000 gigatons is what we get when we try for 350 ppm and miss).

The good news: If one follows the Milankovitch cycles, the next probable ice age would have been around 50,000 years from now, assuming atmospheric [CO2] was no higher than 250 ppm. Under both the moderate and extreme gas release scenarios, atmospheric CO2 will be above 250 ppm, so we can breathe easy, there won’t be an ice age in 50,000 years. Compared with global warming, an ice age is a serious problem.

The bad news: the carbon will take a very long time to leave our atmosphere. Most of it will go into acidifying our rocks and oceans, but fortunately we’ve got a lot of calcium bicarbonate lying around in the ocean (and in limestone on land) to help sequester about 750 gigatons of carbon. This will take a while, and since much of the soluble calcium occurs in things like coral reefs and mollusk shells, we’re going to mess up the oceans. A lot.

Under the moderate scenario, mean temperatures peak a few degrees higher than they are now, and average sea levels 6 to 7 meters higher than they are now, and these maxima will occur perhaps a century after we reach peak carbon concentrations. The reason for the lag is that the oceans will take a long time to respond, because they are so very large.

As we’re finding out, though, the averages don’t tell the story. Some climate scientists prefer “global weirding” to “global warming,” and class the unusual weather we’re having under climate change. And we’ve only experienced about a degree of average temperature increase so far. I’m not sure what saying that global weather will get four times weirder means in real terms, but it probably won’t be pleasant for most people.

The interesting part is how the carbon leaves the atmosphere. Under the moderate scenario, the limestone scrubbers will take about 7000 years to get their 750 gigatons of carbon out. At that point, silicate minerals (granite, basalt, etc) take over. Over the next 50,000 years, they will get [CO2] down to where it is today, and it will probably take them another 100,000 years to get it down to baseline. There’s another Milankovitch-induced ice age lurking out around 130,000 years in the future, and it’s possible that one will happen, if we stick to our moderate carbon release scenario (or rather, if do everything we can to get off fossil fuels now, and fail).

Then there’s the extreme scenario, 5000 gigatons of carbon, all of our oil and coal up in smoke. Temperatures would peak somewhere between 2500 and 3500 AD, at 5 to 9 degrees C above today’s mean temperatures (read weather 5 to 10 times more weird than we have today). Sea level rises up around 80 meters over the next few millennia, with most of that (not all of it) in the first thousand years (that’s right, continual sea level rise for centuries). Ultimately, it takes over 100,000 years for the rocks to sequester carbon to today’s level (and for the sea to drop back 80 meters), and 400,000-500,000 years for a full recovery.

In the moderate scenario, most of the changes take place in the first 1000 years, followed by a long, slow rebound, while in the extreme scenario, the heat and water keep rising for thousands of years, followed by an enormous, even slower rebound.

In both cases, though, the Earth will eventually equilibrate, the carbon will get scrubbed out of the air, and humans will face another ice age. If people are smart today and don’t use up all the coal, our distant descendents may decide to burp another gigaton of CO2 into the air 130,000 years from now, to prevent the next ice age. If we’ve burned through it all, too bad, they’re screwed, and all the polar high civilizations they’ve developed will be ground into forgotten dust by the resurgent glaciers. Since the Earth will have gone through an Eocene-style global hothouse, there won’t, of course, be any polar species left to take advantage of the advancing ice, so the next ice age might be a rather barren place, unlike the last one. But heck, when have any extremists worried about the distant future?

The other fun part of this scenario is how we’re going to live during the coming hot times, which is the ultimate reason I’m blogging here. One technology I’d like to focus on is biodiesel, Craig Venter style. In a recent Wired interview, Dr. Venter talked about the great idea of using algae to make diesel or gasoline. The algae would make diesel precursors, rather than the starches or oils they store now. Nothing too farfetched here, there are companies working on the same idea now, using unicellular marine algae. In the future, it’s quite likely we’ll see huge algae farms springing up in deserts and along desert seascoasts all over the world, where they make diesel using algae and saltwater. It uses non-potable water and barren land. What’s not to like?

The fun part that Dr. Venter didn’t talk about is the carbon cycle. The algae scheme only works if there’s a lot of CO2 in the air. The CO2 will get fixed into fuel by the algae, then burned off to power motors. This isn’t as stupid as it sounds, because diesel and gasoline really are great energy sources. The only limitation will be the amount of sun each algae farm gets. In general, the future gas industry will be solar powered, and there will be rich investors who want to keep a lot of carbon in the air. They may not want to deal with continually increasing sea levels and progressively radically unpredictable weather, but we’ll have to wait and see whether such predictions make them wiser, or not. Regardless, this will be a limited solar age, using gas as a storage medium, not the cheap, plentiful fossil gas we have even now.

Ultimately though, unless people do something drastic about limiting weathering, all that atmospheric carbon will disappear, and the hydrocarbon age will end. This end might happen even faster, if farmers try to sequester carbon into their trees or into their soil (soil carbon helps soils hold nutrients). Personally, I foresee a continual conflict between the fuel industry, on the one hand, who wants to keep CO2 in the air for recycling as long as possible, and nature and farmers on the other hand, who want to sequester carbon in the soil and the rock. A war between air and darkness, as it were? In the end, the world will sequester all the surplus atmospheric CO2 into forms we can’t burn, and if we haven’t weaned ourselves off gas by then, we will be ultimately screwed. Of course, if we have gone post hydrocarbon, humans will be dealing with another ice age.

This gives SFF writers a lot of future to play in, does it not? Anyone want to try playing with it?

Filed under: Real Science Content, Speculation, sustainability, Uncategorized | Tags: climate change, noosphere

To use the high school tactic, if you haven’t heard of a noosphere before, here is Google’s definition: “A postulated sphere or stage of evolutionary development dominated by consciousness, the mind, and interpersonal relationships (frequently with reference to the writings of Teilhard de Chardin)”

This idea crops up a lot in, well, collegiate dorm thinking, and it generally expounds the idea that the world is evolving in stages from inanimate matter towards some grand future where all thinking beings are connected, there’s universal consciousness, the Singularity has happened, or similar versions on the Christian rapture dressed in scientific terminology (Mssr. de Chardin was a Jesuit Priest, so there is a distinct Christian undertone in this whole idea).

I’m going to argue something very different: the noosphere is already here, it’s been growing for over 500 years, and rather than being a rapture of the nerds, it’s becoming quite a pain in the ass, mostly because the sciences it has fostered resolutely refuse to acknowledge its importance.

This whole train of thought was inspired by a quote from William deBuys’ A Great Aridness (Amazon link). In talking about what we learned from Biosphere II, Mr. DeBuys said, “In this respect, Biosphere II proved a true microcosm of Biosphere I, where venality, ideology, self-interest, and other elements of the globe’s political ecology, much more than the workings of the nonhuman world, have generated the greatest obstacles to solving environmental problems, climate change foremost among them.”

There’s that thumbprint of the noosphere: political ecology. Since I’m not a global climate change denier, I see nothing controversial in de Buys’ statement. The “problem” with it is that it lets slip the dirty laundry. Politics matters. Global politics, a signpost of the noosphere of human thought, is now a major factor in the biosphere. Most biologists and ecologists hate this conception, but most would agree that it is nonetheless true. The ecology of politics is another factor to consider, along with the physical world.

Again, there’s nothing new with this idea. The problem is that most scientists want to keep their science somehow pure. Politics happens, certainly, but arguing that politics is integral to a biological study can cause all sorts of problems in fields where nature is considered to exist separately from human thought.

Of course, the noosphere not new. Once Columbus got back from the Indies, human political ecology has been stitching the world together in radical ways (“reknitting the seams of Pangaea” in Charles Manns’ wonderful formulation in 1493). There are whole ethnicities, such as Hispanics, who are the direct result of political ecology. My ancestors have been living in the US since the 17th Century, and my ancestors come from what are now a dozen European countries. National borders (such as the idiotic Border Wall along the Mexican border) now extirpate species (such as the few Baja rose growing in the US), and the most rapidly evolving plants and animals on the planet arguably are pests and crop plants, both of which depend intimately on rapidly changing, human-maintained ecosystems. Political ecology is important.

More subtly and pervasively, the non-human biosphere is dominated by human politics and thought, whether its our effluents causing climate change (“Global Wierding” in deBuys aptformulation), fishing and hunting radically changing ecosystems throughout the world, park boundaries (which turn what used to be huge gradients across which organisms spread into discrete island patches), even concepts of nature which ignore nature outside those park boundaries and guide our actions to favor some species and harm others.

I could go on, and in fact I think it might make a nice book at some point. The problem is that this is a dirty, unromantic conception of the noosphere, one that brings along all the destructive baggage that most of us got into ecology to avoid. It also conflicts with de Chardin’s arguably romantic conception of progress from inanimate nature to a God of pure consciousness. Consciousness (in its human incarnation) is a part of the biosphere now, but the biggest factors right now aren’t our lofty, enlightened thoughts, but rather our worst impulses: “venality, ideology, self-interest, and other elements…”

This is in line with real evolution. While mass extinctions happen (one has been happening for the last 50,000 years or so) major lineages seldom go completely extinct. We add on, rather than proceeding from stage to stage. We’ve still got theropod dinosaurs around (birds), and they’re arguably more common than they used to be. Mammals are an ancient lineage that predates the dinosaurs, and we’re here. So are reptiles and amphibians, along with insects, fish, and so forth. And as Stephen Jay Gould once noted, rather than living in an Age of Mammals, we’re living in an Age of Bacteria, as we have for the last 4.5 billion years. They keep the critical recycling bits of the biosphere working, just as they always have.

What’s wrong is de Chardin’s concept. He saw evolution as progress in stages, from inanimate rock through bacteria, plants, invertebrates, reptiles, mammals, man, then the Noosphere (with celestial, uplifting music, no less). Evolution is more like a compost pile, with new stuff added, often by chance, at irregular intervals, and a pile that continues to churn nonetheless.

So yes, welcome to the noosphere. We were all born here, but we never realized it, did we?

Filed under: livable future, Real Science Content, science fiction, Speculation, sustainability, Uncategorized | Tags: future, green, sustainability

This one’s inspired by this NPR story, about sustainability.

What does sustainability look like? In The Ghosts of Deep Time, I have one character say that civilization is cool, quiet, and green, and that’s still my thumbnail for a sustainable city. To unpack that a bit:

Cool. Forests are cooler than grasslands, not because they get less sunshine, but because they catch more of that sunlight and do things with it. Scientists can actually determine how stressed a forest is by measuring how hot it is. Efficiency translates into less energy loss, which means less heating.

In cities, we tend to waste a lot of energy, which is why they are hot. Most of the sunshine gets reflected, or absorbed into surfaces that it heats up. Most of our equipment runs hot, which means we have to get rid of that heat too. A sustainable civilization doesn’t waste much energy, so it’s going to be cool.

Quiet goes with cool. Much of the noise of modern civilization is wasted energy, gone to making sound waves instead of useful work. An efficient civilization is going to be quiet as well as cool.

Green. This is both in philosophy and color. Plants can perform a large number of functions, from cleaning water to providing shade and cooling air. Moreover, we humans aren’t so far from our evolutionary roots that we don’ enjoy having plants around, even if our thumbs are scummy black rather than green. Obviously, a sustainable city will be ethically green as well, but from a simple design standpoint, I think it’s difficult to have a sustainable city without having a lot of functional plants around.

Anything else? Or can we do without one of these?

Filed under: livable future, science fiction, Uncategorized, Worldbuilding, writing

Simple topic. A few months ago, I self-published a SF novel called Scion of the Zodiac. I just dropped the price and made the first half free. Check it out.

I posted about it on Antipope, where John Meaney guest-blogged about world building. Since I spoke up about it, I figured I’d better provide a venue, in case anyone wants to comment on it.

Criticism is fine, and constructive feedback is much appreciated. Note that “It’s okay,” “I liked it,” and “it sucks,” don’t really qualify as constructive feedback. I’m trying to make the next one better, after all.

Darren Naish wasted a lot of my time in the last two weeks, not that it was his fault. It was fun, actually. I was looking for a distraction, and I found it in his discussion of protobats. I didn’t (and don’t) believe the model he put up there, because it doesn’t make sense. At one end, there’s a nice, tree shrewish gliding animal, and at the other end is a bat, and in the middle is a flying insectivore with big hands. What happens in between?

• It goes from rear-wheel drive to front-wheel drive, which is another way of saying that the antebat (bat ancestor with no aerial modifications) has the strong hindlimbs, flexible spine, and barely rotating shoulders common in mammalian quadrupeds, while bats have enormously strong and flexible shoulders, highly reduced pelvises, and hip joints that have rotated substantially, such that their knees tend to point outwards or even backwards. The protobat (something with a patagium and presumably some aerial ability) would be a mosaic in the middle.

• It goes from a rigid glider to a powered flapper. I think I saw this problem first mentioned in Grzimek’s Encyclopedia, but I’m probably wrong, and it was a decades ago. The problem that someone pointed out is that a flapping flying squirrel doesn’t glide farther, it falls out of the sky, for two different reasons.

–First, there’s the question of how a flailing patagium generates lift, especially when the trailing edge is being held semi-rigid by the hind legs. It will lose lift because the aerofoil is disrupted, and it is unlikely that the forelimb movement will get air under the patagium any faster.

–Second, gliders tend to have fairly long bodies, with the center of mass in the center. Increasing strength in the arms pulls the center of mass forwards. You can replicate the problem by making a wide-winged paper airplane and adding paperclip or staple weights, and seeing what this does to the plane’s flight characteristics.

Worst, the hypothetical protobat does makes all these structural changes while needing to glide. If I was feeling snarky, I’d point out that this is akin to evolving a helicopter from a glider, and it’s certainly evolving an ornithopter from a glider.

The real problem with these ideas is that the intermediate stages look less able than their predecessors. This seems to violate evolutionary theory, which posits that evolution proceeds blindly, favoring traits that increase (or at least maintain) fitness, traits which will spread through a polymorphic population and eventually take over, possibly through isolation. A flapping, mid-weighted flying tree shrew seems to embody the worst of both worlds, since it doesn’t have the advantages of flight, nor does it have the simple stability of a glider.

So I started thinking. If bats didn’t evolve from something that looked like a tree shrew, how did they evolve? I assume that there are two limits:

1. There are no extant protobats. This supports two ideas. It implies that evolutionary theory is correct. If bats were at a selective disadvantage, there would be lots of non-flying chiropterans around. It probably also implies that protobats had an advantage over antebats as well.

2. We’re pretty sure that bats evolved in the Palaeocene, simply because their fossils show up in the early Eocene. That tells us a bit about the environment in which they evolved. For simplicity, I’m going to say that it looks something like modern Papua New Guinea (there’s a bit of research behind this statement, but it’s not germane. Take it on faith for now).

Designing an antebat

It’s probably instinctive for biologists to think of gliders as the antecedents to powered flyers, but this may be problematic. There are quite a few extant gliders, for example, but how many of them launch with their front limbs? The only group I could find are the freshwater hatchetfish, and as noted in the comments on Naish’s blog, they are jumpers, not properly gliders. However, all flying animals use their forward limbs to propel themselves through the air. To me, this suggests that we may mislead ourselves by assuming that the ancestor of a flying animal looked like a flying squirrel.

What other way is there? Let’s look at bats and bat development. I don’t for a second buy that bat ontogeny exactly recapitulates bat phylogeny, for the simple reason that it doesn’t in humans. Enormous wings need to develop first and fastest, just to function. That said, the developing bat fetus does suggest a few possibilities.

First, their wings are very different than the hind feet. This seems obvious, but one possibility is that protobats looked like the so-called flying frog ( such as Rhacophorus nigropalmatus) where all for feet are enlarged. There’s no evidence for this in bats: their hind feet are much more similar among species than their wings are, and I assume that this has always been true. Antebat hind feet probably look like those of extant bats. Perhaps their front feet looked like those hindfeet as well.

Second, it appears that the bat’s pelvis is splayed even in the embryo. People seem to assume that the bat pelvis splayed to accommodate the growing wing, but there’s no particular reason to think that.

Third, modern bats have a massive amount of morphological diversity in their heads, but that has as much to do with echolocation as anything else. Still, I think it’s reasonable to assume that antebats had a reasonable amount of head diversity, to the extent that different species or morphs may have consumed arthropods, nectar, fruits, and tree gums, much as modern bats do.

So what did I come up with?

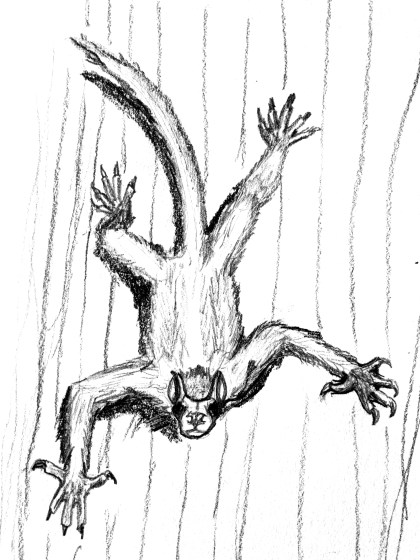

Arachnosorex dubius: a hypothetical antebat

Yes, that’s the dubious spider-shrew, and I’ll be amazed if they ever find it. The name describes both how I think it moved and the niche it held. The images above are my crude sketches of the critter.

In constructing this antebat, I started backwards. What if, rather than the patagium coming first, the hip and shoulder alterations came first?

Are there any animals that have powerful front shoulders and outward pointing knees, and second, are there any advantages to this configuration? Bats have these characteristics, (as do spiders and other non-mammalian animals). Many bats are quite good on vertical surfaces, even ceilings, and they cling well. Something like a vampire (Desmodus rotundus) moves well on the ground, on walls, even on rough roofs, and can launch itself into the air using the power of its forelimbs. The advantage of those backwards pointing hind feet is that they make excellent grappling hooks. An antebat with strong forelimbs and backwards pointed hindlimbs would be quite agile on a variety of surfaces, whether face up, face down, or sideways. However, it gives up some speed for this maneuverability (since it gives up that characteristic mammalian gait, the gallop), so the antebat would be limited to areas like tree-trunks (on the bark or inside a hollow tree), on thin branches (especially the underside of branches) and in caves—in other words, places we find bats now.

This satisfies the first criterion, that bats outcompeted their predecessors. Here I’m suggesting that antebats exploited the same types of food sources as bats do now. Since bats are faster (through flying) than antebats, bats also have a comparative advantage. Additionally, these types of habitats were available in the Paleocene, so it satisfies the second criterion

From nose to tail: the spider-shrew’s head is based on a primitive fruitbat, with a smaller braincase but still well-developed eyes. The forelimbs are well developed, but there is little enlargement of the hand. The hindlimbs are splayed, and the spider shrew overall has a semi-sprawling posture. However, it can move effectively on the ground. The tail is thin and fairly stiff. Its primary function is to act as a support when the antebat is climbing.

Instillator hypotheticus: the dropper, a hypothetical protobat

This “hypothetical dropper” was inspired by a fruitbat photo I found on Flickr. In this case, the patagium is developed, but I see no reason why it should have a hairless patagium.

Here I suggest that antebats became protobats by developing long-distance jumping and falling as an efficient defense and as a way of covering long distances. This lifestyle change hinged on developing more powerful forelimbs and better vision (echolocation evolved after bats flew, according to the fossils). While yes, I’m suggesting a gliding intermediate, in this case, I think it’s likely that protobats powered their takeoff jumps with their forelimbs, not their hindlimbs. They saved on weight by making their bodies more compact and their limbs longer, as seen in modern bats. Probably finger elongation started initially as a way of increasing patagium area (as here, with the dropper), and protobats early on developed the folded wrist we see in modern bats, effectively climbing on the backs of their wrists, with their thumb claws providing the support of the five claws of the antebats. It’s also possible that the uropatagium developed with the arm membrane, giving a “three-winged” form to glide with before ultimately developing into the bats we know today. The advantage of the three-winged form is that there is a separate wing structure that, combined with the highly developed shoulders the protobat inherited from its antebat ancestors, can lead to ultimately to powered flight. The more Instillator develops its forelimbs, the better it does.

Diet wise, I suggest no change from antebats to protobats. The protobats ate the same food as their ancestors did and their descendents will. As with the spider shrew, this satisfies both limiting criteria.

Wow, that took way too long, but I’m back.

I’ve got a simple problem, and I’m posting it here in the hopes of some new ideas.

Unfortunately, this isn’t science fiction. On the up side, it might have a tech solution.

While I was reading those environmental reports, another problem showed up. That problem came from a friend who is also an environmental consultant. He’d been called in to salvage a couple of rare plants (and I’ll get to the stupidity of that in a moment), because the environmental paperwork said that was all that was on the site of a small housing development. Actually, the site had about an acre of really rare stuff, including a couple of endangered species. However, the grading permit had already been issued, the paperwork had been signed, and he got to pick the two plants he was going to save (not including the endangered ones, as they officially didn’t exist). To top it off, the rare species he was salvaging doesn’t survive transplantation, so this was a pointless gesture, just killing them slowly instead of bulldozing them.

So here’s another way developers keep their costs down: hire someone to lie on the paperwork. These liars are called biostitutes or conslutants in the trade, incidentally.

My group is trying to figure out how to catch these creeps. To gather evidence, my thought was to post the environmental documents online, and to get volunteers to take pictures and GPS points to show where the pictures were taken. Then we can compare what they wrote with what is actually there.

It it turns out that a lot of developers are lying, I do know some people in the local bureaucracies who are going to get very, very angry. Whether they can do anything depends in part on who’s in power, but we’ll see.

But that’s the question: what can my (small, volunteer) group do using low cost technology? How do we gather and use information about this problem, without getting sued by a developer?

Matt and whoever else, spread the word: I’m trying to crowd-source solutions on this one, and I’m pretty sure we’re not alone with this issue.

Filed under: Uncategorized

…Are actually the sounds of me silently cursing a bunch of developers. I’m volunteering for an environmental group, reviewing some environmental impact statements that are due in a few weeks. Sigh. They’re all simply lying on the biological parts of their statements. The only reason they get away with it is that the environmental community is spread too thin to call all the idiots on their bad projects.

One of these steaming piles is a big, public project. If they had just followed the Endangered Species Act and other relevant environmental laws, it would probably have been cheaper than what they’re going to end up spending on the lawyers (assuming someone sues, which is likely). It would also probably be designed better. And your standard biologist costs bills at 20% of your standard lawyer.

The lesson for the business community is to get the biologists, archeologists, and other experts in at the initial design phase, rather than hiring some conslutant to greenwash a bad design after all the major design decisions are made. I much prefer helping a developer design a cost-effective green community, rather than doing these reviews. It’s fun to save client money and the environment at the same time.

Yes, following the law is cheaper and results in better projects. Amazing, isn’t it?

Blogging will resume after I finish this mess.

Filed under: Uncategorized

I normally don’t pay a lot of attention to politics, but when I see reports arguing about how many people showed up for some Tea Party event in Washington to somehow mark the anniversary of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, I get…well, what?

Annoyed, certainly. But this is so typical, I really don’t want to spend the energy. What’s the description for just wishing that a problem would go away? I don’t particularly want to ignore it. I just want the people involved to spontaneously combust, so that the rest of us can mourn their passing and getting on with our lives.

Rather, I want all the talking-head reporters covering Washington (yes, I’m looking at you NPR) to understand that there’s this thing called reality. Reality generally has numbers attached to it. One set of numbers, with an error bar as needed.

It seems that the Conservative segment of US politics has wholeheartedly embraced magical thinking. As defined by me, this is the idea that you can through special knowledge and practice, change reality, mostly by changing how you see it.

Remember good ol’ Bushie II? He seemed to run on the idea that if he said something, it was therefore true, especially if he could threaten anyone who disagreed with him. That’s the playbook we see now: bullshit (or lying when they care about the truth), threaten those who disagree, and keep reinforcing the story up until it becomes people’s consensus reality.

This is magic, and unfortunately, it works. It’s also not new: if you look at spell, enchant, charm, glamour, even fetish, you see that these all describe types of media manipulation. People often think that our ancestors were stupid to believe in magic. They weren’t: what they called magic was when a slick-talking stranger came to town and drew up a paper that said that the land they had farmed for generations now belonged to some other dude. And they knew they couldn’t fight him, because they didn’t know how to spell. Only the truth would set them free, and all to often, their church told them that they owned that truth too, bound up in the words of the Bible. Magic is a perfectly good way to describe such a world, when you’re ignorant and powerless. The fact that people still use it today should leave us wary, not complacent.

What’s fascinating to me is how inefficient this type of magic is: No one is sure how much the Koch brothers (link to New Yorker article) are spending to bankroll the Tea Party movement, but it’s a lot. And it’s not terribly effective, despite the noise.

Still, it sucks that so many angry people are getting manipulated so badly, conned into parroting the interests of a group that demonstrably do not have their best interests at heart. Unfortunately, this group would be perfectly willing to destroy my life in multiple different ways, so I’m not that sympathetic.

But all things considered, I prefer the cold iron of real numbers. They’re more useful than the magical BS these dudes are promulgating.

Filed under: Uncategorized

I must admit, I love this title, because it says everything that’s wrong with ecology these days. Right. Don’t worry, this ends up in science fiction in about seven paragraphs.

The title comes from the August 2010 issue of Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, which fortunately for all of us is available free online. This journal is published by the Ecological Society of America (yep, I’m a member), and it’s about all the problems ecologists, climatologists, and environmental scientists are having getting the public to tune in to reality. And yes, that’s my bias.

But the interesting thing for me is how much a culture clash there is. Back as a grad student, I got a paper bounced from several publications on the grounds that “we don’t publish speculation.” To their credit, they did publish a mathematical model I created, but this mindset was fascinating. Some of these people were colleagues of a late, lamented giant in that field who said something like “evolutionary biology is for people who can’t do field science.” Since I respect his field science a great deal, I won’t name him. However, this refusal to deal with the past, or to play with conjecture, was and is striking.

Back to the Frontiers in Ecology articles, on “Effective Communication of Science in Environmental Controversies.” It made me sigh, because it’s so earnest. My favorite is the shortest, Katherine Ellison’s ‘Media mea culpa’. She’s a professional journalist, and she points out the problems the media have in covering environmental issues.

Two quotes particularly stand out:

“’The great need isn’t to explain the science one more time, as many reporters seem to think’, says David Roberts, who covers climate-change issues for the online magazine, Grist. ‘People just can’t absorb it unless they can picture a reasonable way out.’”

and her closing thought:

“Averting the worst climate-change scenarios will require nothing less than the systematic upheaval of our economy. My hope is that we journalists still have time to help lead the charge, instead of merely being swept up in it.”

This is where we get to the culture conflict and science fiction. Science fiction, to grossly oversimplify, uses the future as a setting, and when it inspires, it seems to inspire mostly the wonderful gadgets and scenarios that inspire young readers to go into the technology fields to create these things. Love it or hate it, Start Trek has inspired loads of engineers, as did Neuromancer (cyberspace) and Snow Crash (Second Life).

Ecologists tend to get into their science by reading John Muir, or by those long hikes their families took when they were young, and they tend to get radicalized when they see their favorite areas trashed. Many have read science fiction, but now days, they are too busy saving the world (ideally), or at least trying to keep employed (speaking for myself).

Beginning to see the disconnect between cultures? While there are whole subfields of disaster science fiction, the future inspires SF. In ecology, the past inspires, and the future is the problem. To make it even more explicit, I’ll point to a question from Don Fitch to John Scalzi the current president of the Science Fiction Writers of America, a few months ago:

from Don Fitch: ” Plants. I’m pretty sure you’re not A Plant Person — not much beyond lettuce, tomato, onion on a hamburger, or grass; a small tree in photos of sunsets — but I’m wondering if you’re as virtually-blind to plants the way some s-f writers/readers I know are.”

Scalzi’s answer: … “So, no, I don’t think I’m virtually-blind to alien flora, but I do think alien flora on an earth-like planet (where many of my books take place) will be at least slightly familiar.” (I cut out the rest).

Oh dear. It’s not a question about alien plants, John, it’s about whether you see the world around you.

I like Scalzi. He’s one of the more ecologically aware major authors out there. He deserves credit, but the thing that sucks is that there are so few authors like him. And even he may have trouble seeing the trees outside his window, unless a camera is involved.

Sigh.

To oversimplify, we have ecologists who don’t like the speculation on one side, and on the other side, we have science fiction writers who, as a group, are thought to be tree-blind if not totally clueless about anything that isn’t shiny.

We also have declining readership of science fiction.

To me, this looks like a couple of problems that have a common soluton. The environmental community is stuck with doom-and-gloom as their deeply engrained belief in the future, and the science fiction community has a lot of trouble imagining a future that realistically solves the problems we all know are out there. Part of the problem may be the publishing culture of science fiction, rather than the authors, but still, good environmental science fiction is scarce, and it even more rarely gets wide readership.

Recently there was Scalzi’s Metatropolis and Jason Andrew’s Shine, both collections of short stories. And…I’m not sure what else. Did any of you read either of these? They’re not bad.

So the question for discussion is: what does a reasonable future look like? Can we bridge the cultures of the ecologists and the futurists? Or do we see both of them, bashing their heads on opposite sides of the same brick wall?

And while we’re at it, can we have some of the writers from Wired go over and help on the titles of Frontiers? “Effective Communication of Science in Environmental Controversies” is a sleep aid, not a phrase that gets me motivated.

Filed under: Uncategorized

Hi All,

Since I’ve been having fun commenting, I thought I’d make space for others to return the favor. As the title says, I’m interested in putting back the life back in science fiction, otherwise known as encouraging SF and fantasy writers to pay more attention to this world and to their own. My background is that I have a couple of advanced degrees in ecology, and I’m happy to field questions and discussions.

What I’m going to post here is what I’m missing in what I read these days, both in print and online, and what I like to see in literature. Feel free to agree or disagree. This blog is strongly pro-science. It isn’t anti-religion, anti-fantasy, anti-imagination, or anti-humor. I just think that most people suffer from the green blurs, and I have ideas about how to cure that. If you’re allergic to discussions of evolution or ecology, this won’t be a comfortable place for you.

While I assume that everyone’s an adult here and I value a diversity of opinions, there is a sun-blasted courtyard over there where I do experiments on troll postings. If your post disappears, it’s because I thought it would make suitable experimental material. And yes, the experiments are destructive.